Why Design Patterns

I’m at a moment in my developer journey where knowing design patterns is important. Understanding exisiting code, making sure to write new clean code, being able to communicate with more senior developers…

As a self-taught developer, I never really went deep into those subjects. I heard some of the patterns names, used it a couple of times but that’s it. So, now that I decided to learn them properly, I’ll share my journey with blog posts like these. Maybe you’ll find them of some use, or you might even correct me if there are some mistakes ;)

Note: Code examples will be in Java because that’s what I’m using in my work, and what my learning material uses.

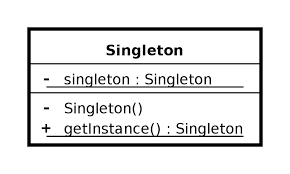

Singleton

The concept

A Singleton Pattern ensures a class has only one instance, and provides a gloabl point of access to it.

A Singleton, like its name indicates, is an object for which there is only one instance. It’s purpose is to make sure that there is only one instance of a object running at all time.

It’s an important concept because some objects (like objects that handle logging or thread pools or caches for example) only need to be instantiated once. If you have more than one instance, it could create issues (logging the same things several times) and consume a lot of resources. On top of that, we have to make sure that our object is created only when we need it. There would be no point in creating an instance if the object is not used right away. This is one of the differences with a simple global variable.

Question is, how do we do that?

How

- The Singleton class is the only class that can instantiate itself because the Singleton class constructor is private.

- The Singleton class, therefore, is the only one that manages its instance.

- Other classes can’t create an instance of a Singleton. They only call the Singleton class. The Singleton class creates the instance (or returns the existing one).

Let’s look at a code example:

public class Logging {

private static Logging instance;

private Logging(){}

public static Logging getInstance(){

if(instance == null) {

instance = new Logging();

}

return instance;

}

// Other Logging methods...

}

Here is a Logging class. For my purposes, I only want one instance of this class running at all time.

You can note that the constructor private Logging(){} is indeed private. This class can’t be instantiated from outside the class.

The getInstance method is static, meaning it’s a class function and can get called anywhere with Logging.getInstance(). This is the method other classes will use to retrieve the Logging instance.

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Logging LoggingInstance = Logging.getInstance();

// This next line will fail! Constructor is private!

Logging PleaseCreateInstance = new Logging();

}

}

And that’s how things would work. You would call the getInstance method to get the Logging instance to call other useful Logging methods. The new keyword would throw an error because the constructor is private! Awesome.

Multithreading

But what about multithreading? What if two differents threads access the Logging.getInstance() method at the same time? If both threads do not find an existing instance, they will each create a new instance. Therefore, you end up with two different instances of the Logging object… So much for being a Singleton huh…

You have a few options.

synchronized keyword

Java allows us to make synchronized methods by using the synchronized keyword, like so:

public static synchronized Logging getInstance(){

if(instance == null) {

instance = new Logging();

}

return instance;

}

This will make sure that every thread will wait for its turn before entering the method. So, if two threads want to access getInstance at the same time, we won’t create two different instances.

One problem with this approach: it’s fairly expensive to synchronize the getInstance() method. Because every thread has to wait its turn, it creates a bottleneck when threads (or even a single thread) have to access the method. Plus, you really only need to synchronize the getInstance method at the creation of the Singleton, not once the instance has already been created.

Create the instance when the class is loaded

Another approach you could take is to eagerly create the instance. Actually, our code lazily creates the instance. We wait for the method to be called to create the instance for the first time.

We could modify the code like so:

public class Logging {

/* Create our instance, now it doesn't matter

if we have several threads calling the getInstance

method at the same time */

private static Logging instance = new Logging();

private Logging(){}

public static Logging getInstance(){

/* We always have an instance now, so we just return it right away! */

return instance;

}

// Other Logging methods...

}

With this approach, this is the JVM that creates the instance when the class is loaded, and before any thread can access the method.

Use double-checked locking

Double-checked locking fixes the problem mentionned earlier by the synchronized keyword. It allows us to synchronize the method only if no instance has been created.

public class Logging {

private volatile static Logging instance;

private Logging(){}

public static Logging getInstance(){

if(instance == null) {

synchronized (Logging.class) {

if(instance == null) {

instance = new Logging();

}

}

}

return instance;

}

// Other Logging methods...

}

First, notice the volatile keyword for our Logging variable. This keyword makes sure that multiple thread handle the instance variable correctly when it’s being initialized in the Logging instance.

Then, in the getInstance method, we synchronize only if we do not have an instance. In other words, we are able to synchronize the first time through the method only. So, if we already have an instance created, we do not get inside the first if block, and we do not get to the synchronized code, saving us from the bottleneck problem.

Note: This method will not work for Java 1.4 or earlier.

Conclusion

Despite its apparent simplicity, the Singleton’s implementation can be tricky and we must be aware of the details. Things like multithreaded applications, the JVM version, the resource constraints or the number of class loaders can impact the way you implement this pattern.

Have fun <3